An Exercise

Memories on a Graph

Find Your Why

Simon Sinek states in his book Start With Why that every individual has a single passion that drives them forward in life. And I don’t mean a passion in the context of things one likes to do like swimming or golfing. Instead, Simon’s talking about something deeper that motivates a person their entire life. A sense of purpose.

In Simon’s Ted talk, How Great Leaders Inspire Action, he describes the golden circles and an approach to thinking about this motivation. He would later write a book about it which dives in more depth of this topic and includes examples and stories of how people’s “whys” have taken shape. If you haven’t seen the Ted talk, I highly recommend you take a listen and perhaps become inspired yourself.

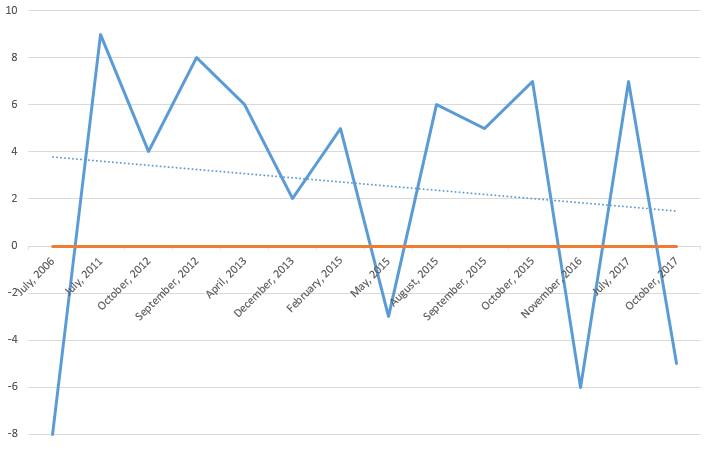

Simon would later write a book entitled Find Your Why with a motivation of assisting individuals in finding what motivates them. In going through this book, I’ve been asked to write down various memories that have influenced me throughout my life with an objective if finding patterns and similarities between them. And though it wasn’t asked in the book, I thought it’d be interesting to graph them on a timeline based on their level of influence, whether good or bad and see if any trends occurred.

Unfortunately, and a setback of the process, that friend needs to be instructed on how to dissect these stories as to align with Simon’s motivation. At the moment, I have yet to find someone who is familiar with Simon’s findings and haven’t been able to make progress past this stage. That said, in attempts to move forward myself, I’ve started writing the memories myself and figured I’d share a few of them with you.

WIMPGives

WIMP, or the Web Interactive Media Professionals, is a community of nerds with backgrounds in programming, design, development, business, and various other fields. What started as a small gettogether with friends ended up spawning into a community of technology enthusiasts who understood that sharing knowledge benefited everyone. In 2013, WIMP decided they could use their membership to help the world.

Not that long ago, building a website was a one-person job. That person would write the content, design the layout and art, develop the code, and publish to the world wide web. A single person could realistically take the project from start to finish without needing much more help than a few applications. The title of “webmaster” was born. And while this may still be true for many small sites, the sophistication of the internet has grown—and with it the complexity. What was a one-person job was now turning into a job for five, each with specializations in different areas of web design. The problem is, a five-person team is much more expensive than a team of one.

WIMP understood this problem. They understood that the increased cost hindered organizations that did good for the community but didn’t have the funds to pay for their efforts. They also understood that, right in their own pocket, they had was the needed to help these organizations. And in 2013, they launched their first charity hackathon.

The atmosphere in that warehouse was incredible. Members of different backgrounds and skillsets were divided into teams. Each team was then paired with a charity. Now, most people will tell you building a website is a time-consuming process typically taking weeks, months, or longer for larger projects. At WIMPGives, the goal was simple: build our charity a website in a single day for free.

Most of us had seen each other before. Some of us were even friends. But the majority of us might as well have been sitting in a room of strangers. And with only 10 hours to go, time for introductions was limited.

The passion in that room was tangible. You could throw a basketball at the heads of anyone and they wouldn’t lose concentration on keeping pace. Decisions were made quickly to stay in competition with the other teams. Debates on how to best proceed were settled quickly because there wasn’t time to bicker. And despite all the difficulties and hurdles of a one-day website, progress was taking place in the form of pure focus and passion.

In the following years, I participated in the event twice more. That final time, my role was upgraded to team lead, a role fulfilled by other individuals in the previous two. It was that final event that we took first place and won the competition for our charity. I’ve had proud moments in my career, but this one is near the top.

The Witness

When I tell people I play video games, they usually think of large titles like Grand Theft Auto, Call Of Duty, or some other large-budget action thriller seen in commercials. And why wouldn’t they? These games are hugely profitable and widely known. Grand Theft Auto 5 alone had a budget of $265 million dollars, the budget of about nine La La Land’s. And don’t get me wrong, I enjoy Grand Theft Auto as much as the next guy—but it doesn’t inspire me.

Over the last decade, the barrier to entry in developing a video game has become increasingly easier to overcome. What used to be a market for just AAA titles is now embracing a pivot to focus on indie developers and individual creatives. With this in mind, these games don’t have the revenue to make better graphics. These companies can’t create large digital worlds simply because their team isn’t large enough. Instead, they have to compete in creativity. While Call of Duty focuses on competitive gameplay, indie games focus on storytelling. And while large studies publish low-risk sequels guaranteed to make money, indie games reject this philosophy and build something unique. So when I tell people I play video games and they think of Grand Theft Auto, I can’t help but feel they’re missing out.

Introducing The Witness, a game released in early 2016 by a guy named Jonathan Blow. At first glance, the Witness is a first-person puzzler that releases the player into a world with no instruction, objective, or storyline. Instead, the game focuses on the experience of discovery. The player has to uncover how progress is made and, truly, how the game is designed to even work. Without giving anything away, the experience is so focused on discovery and mystery, that any other standard game mechanic would be considered a distraction. There’s no music, dialog, people, or even strategy. What it does have, however, is intellect.

The best way I can describe what makes The Witness different is to use the example from the movie The Sixth Sense. Remember when you watched it for the first time and the twist ending hit you in the gut? It was shocking. It hits you hard. And it makes the experience. It was this feeling that occurred during a certain discovery when playing… except it happened twice. The first was about six hours into the game, the second about double that. To feel it once makes the experience. Experiencing it twice, that’s impactful. It influenced me. And I’ll probably never find a game like it again.

The Tubbs Fire

At about 5am, I found myself standing outside my home on an October morning. I remembered hearing sirens throughout the night but didn’t think much of it given I lived near a relatively busy street. What I hadn’t realized was, about 6 hours previous, a fire had started, grew, and now illuminated north-western night sky with a dull glow. I would later learn the Tubbs fire would consume 2,800 houses and take away the homes of 5% of my town’s population, but for the moment, I just stood there thinking about my what I had to do. It all seems to clear in retrospect but, when you’re in the moment, it’s hard to comprehend the gravity of the situation. I scanned the street to see my neighbors watering down their houses or loading their cars with belongings and memories. Other houses were quiet and I couldn’t help but wonder if they were still asleep, unaware of the circumstances, or if they had already left to find somewhere safe. Should I be doing the same? Should I start packing my things in my car to leave behind my residence to live out its own fate?

I laid out two large bags and a suitcase on my bed. I didn’t have much room but, on the other hand, I didn’t have much stuff. I grabbed some essentials in case I ended up living out of wherever for an unknown amount of time. I packed a few small memories that could easily fit along my things. After that, I started packing expensive things including a couple laptops and a few hard drives with client data and work history. And with all that packed, I still had a bag left.

I stood there trying to prioritize what I should bring and I couldn’t do it. My stuff, what seemed so important to me the day before, I now realized truly wasn’t that valuable to me. It was just stuff. Stuff that, in a moment of extreme circumstance and clarity, I no longer cared about. Stuff that was nice to have but didn’t help fulfill me as a person. Stuff that was replaceable.

And I left.

I would eventually come back to my home finding all my belongs where I had left them. My life ended up being relatively untouched, I’m grateful to say. Truly, the only thing I have to complain about is being inconvenienced for those few days, a statement that would normally be laughable in lighter circumstances when compared to those that lost their homes. The Santa Rosa Tubbs fire is now known as the most destructive fire in California history, destroying 5,643 buildings and ending the lives of 22 people. Somehow, being mildly inconvenienced doesn’t seem too significant.

It’s a humbling thought to learn your stuff is just stuff. Everyone says it, but this was the first time I had truly experienced it for my own. And since that event, I ended up donating a lot of it. I’d like to say my motivation was was to help those in need—and much of it was—but, truly, I simply no longer wanted it. After walking back into my room, it felt like I was looking at the belongings of someone else. I felt anchored and trapped under the weight of old things. And now that much of it is gone, I felt liberated as if starting fresh without the limits of a previous time. I felt good about whom I’ve become and no longer needed my things to help define my value. I felt free.