UX Design Process

Methodology

High level stuff

Workshops

What is UX?

UX (User Experience) design is the process of creating a product that’s both usable and desirable. While many definitions attempt to incorporate outcomes of UX design within the definition (e.g. ease of use, talking with customers, designing with empathy, etc.) what’s important to know UX is a process with no single track of success.

UX design is one of the rare positions that prioritizes having knowledge in an array of horizontal skills over significant depth in any particular vertical. One is expected to have experience in web design and development, user research, graphic and interaction design, product development, and potentially even some project management and marketing. The real art of this position lies in utilizing all this knowledge to create a cohesive workflow to build a product that’s functional and enjoyable. To top it off, this workflow often changes from project to project depending on the product requirements and the skill set of the team.

UX In Marketing

While this particular page is geared toward defining the role of a UX designer, it’s important to understand the realms of UX and marketing overlap in many of the same areas. An accurate definition of marketing—similar to UX—is another debated topic that seemingly has many answers. Despite the complexity, the best and most concise definition of marketing is the ability to capture a perception in the mind of an audience. This definition includes various areas of marketing including sales, advertising, public relations, and branding; all of these areas being able to change perception. More importantly, this definition also includes entities outside of business including politics, religion, activism, and ideology—all of which require marketing in some way.

Though the goal of a UX designer is to create a product that’s usable and desirable, the methods of how one achieves that result include talking to customers, understanding their needs, measuring a product’s effectiveness, and iterating for improvement—all tactics of marketing. Long story short, while not commonly associated with the role of marketing, the mindset of both departments share more in common than most realize.

Knowing this, it’s not easy to determine where a UX designer “fits” in a company or even what department they should be best located. UX designers work directly with graphic artists, business stakeholders, programmers, and project managers—all of whom will typically be placed in different locations within a large organization.

In the case of the corporate structure who’s teams are department-based rather than project-based, I believe it makes the most sense for them to be located within marketing where their research can be best utilized and shared. In the case of a project-based organization with dedicated teams, the department-based hierarchy no longer applies.

Lean, Agile, and Scrum

At their cores, Lean, Agile, and Scrum are good methodologies to follow and provide an assortment of benefits for any team. While they all have similar motivations, it’s important the difference between them are understood and why they all work together.

“Lean” is the methodology of building a product using the minimum amount of effort possible. While the history of “lean” goes back to the Toyota assembly line in Japan during the 50’s and 60’s, all one needs to understand is no productivity is wasted while no effort is misplaced. Simply stated, there is a process that allows a specifically focused team to build a product in the least amount of time.

“Agile” is a methodology that allows a team the opportunity to pivot a product at any given time. Products are built and placed in the customers’ hands quickly as a method of testing it’s effectiveness and value. This provides the ability to fail quickly, cheaply, and allows a team to decide if they want to continue the current plan of development or pivot another direction.

Finally, there’s “scrum”, the most intricate of the three. Scrum is a topic that can go deep for those who wish to spend the effort. At it’s core, Scrum is simply a communication strategy. While we could talk about the different roles it bestows upon each team member, what’s more important to know is that each team member must be in constant communication with the rest of the team. The Scrum process mandates short daily meetings (called stand-ups), bi-weekly planning meetings which discuss what the team is working on (called grooming sessions), and an end of project meeting that talks about what worked and what didn’t work (called retrospectives).

Additional Reading...

Scrum is a topic that could be talked about for a long time. If you’re interested in learning more check out Scrum by Jeff Sutherland and J.J. Sutherland and Scrum Mastery by Geoff Watts.

For more on Lean and Agile, consider The Lean Startup by Eric Ries as well as The Lean Product Playbook by Dan Olsen.

Research

User Research

– Zip Tapestry

– Analytics

User Interviews

For qualitative research, user interviews provide a great balance of high-quality information for a relatively small amount of time. Despite what is often said, interviews don’t even have to be expensive. In fact, those who are willing to be interviewed for a cup of coffee are typically able to give more personal and sensitive responses. Instead of prioritizing a financial reward, they receive a benefit in the feeling of accomplishment in helping a product become better.

The objective of a user interview is to gain an understanding of who the customer is, what are their desires and needs, what objections and hurdles they need to overcome, and what about their lifestyle attracts them to your product. The interviewer should walk away from the conversation able to empathize with the customer and their position.

While there isn’t a set list of questions that works for every interview or project, there are a few guidelines that can be followed to make the interview run more smoothly for the customer as well as more valuable for the business.

Ask Open-Ended Questions. The main advantage of a user interview is the ability to deeply explore any direction the conversation might travel. This benefit is completely negated if the questions being asked only require ‘yes’ and ‘no’ responses. More importantly, asking a question with such a limited answer may not just give you less information, it may even present the answer in a way that allows misdirection.

For example, let’s say a company is attempting to build a car and gain a better understanding of what struggles their customers have on their daily commute. The company might ask the user, “Do you ever struggle with Traffic when traveling to work?” to which the user might respond with, “Sure, there’s always traffic in the morning.” With this information, the company might go back to their product design team and begin working on a vehicle that allows them to get to work more quickly—perhaps a smaller car that allows them to weave through traffic more quickly.

If we instead asked, “Why kind of struggles do you have when traveling to work?” the user might respond with “it’s difficult to hear the radio due to all the external noise.” With this information, the product design team might want to design a vehicle with better sound protection. The user ended up not minding the traffic because it was the only part of their day they got to be completely alone. Making the vehicle smaller and faster—while still may have been appreciated—was the wrong direction for the product design team and a distraction to the users’ actual desires.

Lastly, I wish to mention one of the most common mistakes I’ve seen when interviewing customers is the focus on the product rather than the customer using the product. While understanding a user’s interactions with the product is important, the motivation should be to better understand the needs the user is attempting to solve. Once this is learned, the interviewer can then follow up with questions regarding the product and how the customer uses it. Without understanding their needs, the information won’t be that helpful.

Below is the list of interview questions I asked when attempting to better understand the audience for Professional Marketing Group (PMG).

- What is your current job and what do you do there?

2. How long have you been in that position?

3. Do you have a formal education in marketing or another field?

4. What kind of struggles do you have in your day-to-day?

5. What are your career aspirations?

6. Why do you come to PMG events?

7. What do you find most appealing about PMG?

8. Are you comfortable coming to PMG events? Why/why not?

9. Besides PMG, what other ways do you stay up-to-date?

10. What kind of tools do you use at work?

Surveys

For mixture of quantitative and qualitative research, surveys provide a simple and affordable method of receiving feedback from a large audience. Because surveys have the benefit of being automated, attaching a survey to a product or at the end of a phone call can provide a diverse and honest reflection of a user’s experience.

While sounding like a great solution on paper, surveys come with one major hurdle: nobody wants to do them. People find them cumbersome, time consuming, and hang up the phone the moment they survey is prompted. The good news is there’s a fairly easy way to bypass this hurdle while still achieving the desired outcome.

Firstly, don’t call it a survey. Rather than asking 10 questions in a survey, instead ask the user, “Can I ask you a question?” and provide them a prepared question off your list.

Secondly, only ask one question at a time. While this method doesn’t generate answers to the entire survey in one go, it communicates to the user the survey won’t take up too much of their time and allows the questions to trickle in. If the choices are either not having surveys filled out or having them come in a piece at a time, the trickle method is the wiser choice.

Focus Groups

One of the final forms of user research not yet mentioned is the application of focus groups. For those unfamiliar, focus groups gather a selected number of people—typically a pre-qualified list of people—gather them into a single room, and ask them questions as a unit. The motivation of a focus group is to acquire both qualitative and quantitative research within a single event saving the company both time and money. However, like most tactics, focus groups comes with it’s own list of pros and cons.

Firstly, focus groups—specifically those who pre-determine who is invited—frequently miss the purpose of qualitative research. The objective of market research isn’t to ask the general populous about one’s product but to only ask those with whom the product is targeting. Exploring the diversity of your audience is important, of course, but make sure the diversity is within the boundaries of the product.

Secondly, focus groups often tend to be poor solutions as a whole. Similarly to every classroom, those in the group who are more outspoken receive the most attention. Inadvertently, those same individuals end up controlling the conversation, biasing those around them, and potentially end up speaking for the whole. When gathering qualitative data, tribe mentality needs to be avoided—user interviews simply do this better.

For quantitative data, surveys provide a superior reach while having the additional benefit of potentially being free. And thanks to the modern days of automation, the amount of effort required ends up being minimal.

Brand Drivers

To start off with our user research, let’s talk about Brand Drivers, what they are, and why this is the ideal starting point for understanding your customer.

For our purposes, we’re defining a brand driver as a specific benefit a customer receives from using your product. Those benefits “drive” and attract users to your brand. Once we fully understand all the potential benefits the product can provide, we can narrow down exactly which provide the most value and feel the most important to our customers.

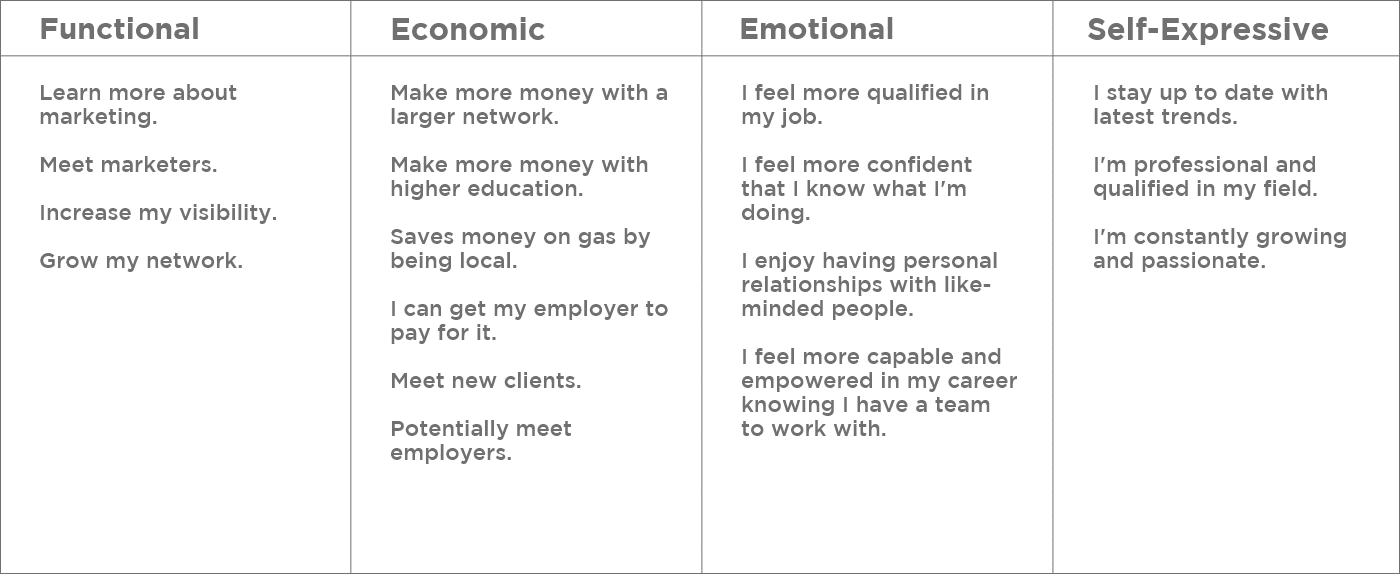

Let’s start off by drawing a table on the board with four columns and the following headings: Functional, Economic, Emotional, and Self-Expressive.

Let’s define each of the column headings.

Functional benefit – The purpose and result of the product. A functional benefit of a car is it allows one to get from point a to point b.

Economic benefit – How it benefits the user financially. A financial benefit of a car might be that it saves them more money by not having to spend as much on gas.

Emotional benefit – How it affects them emotionally. An emotional benefit of a car might be that it makes them feel powerful and secure.

Self-Expressive – What they’re emoting to the world about themselves. A self-expressive benefit of buying a car might be that it expresses to the world they’re prestigious and have high status.

In each column, start listing all the potential benefits for each category. This process is ideally done with 3-5 people with one person acting as moderator for the group. If you are the moderator, it’s important to write down relatively specific benefits while staying away with generics.

For example—continuing our car analogy—it might be suggested that a functional benefit of a car is that it gives the user the ability to drive. While accurate, it fails to empathize with your potential customers and understand their core needs. In this case, the moderator should ask, “Why is that important?” to which the person might respond, “So they can get to and from work.” The benefit of ‘getting to and from work’ is a much more valuable to the customer than simply driving and gives us a better understanding of the problems the user is attempting to resolve.

Focus on quantity over quality. Bad ideas will be ruled out in a later step. For now, it’s more important that all ideas be considered—particularly if mentioning them sparks conversation.

Here’s one I made for PMG, a marketing group that hosts educational lectures and mixers.

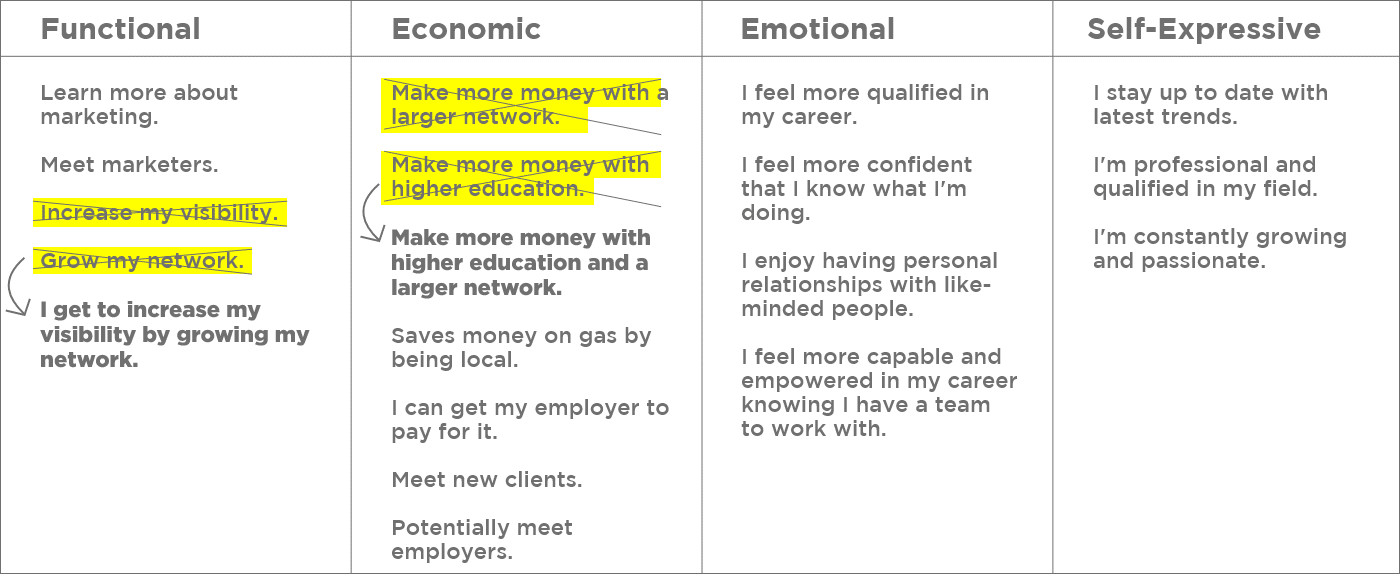

Now that we have as many benefits as possible written down, go through each column and remove any redundancy. Benefits that are similar and have related motivations can be combined into one item. Don’t, however, combine benefits between columns.

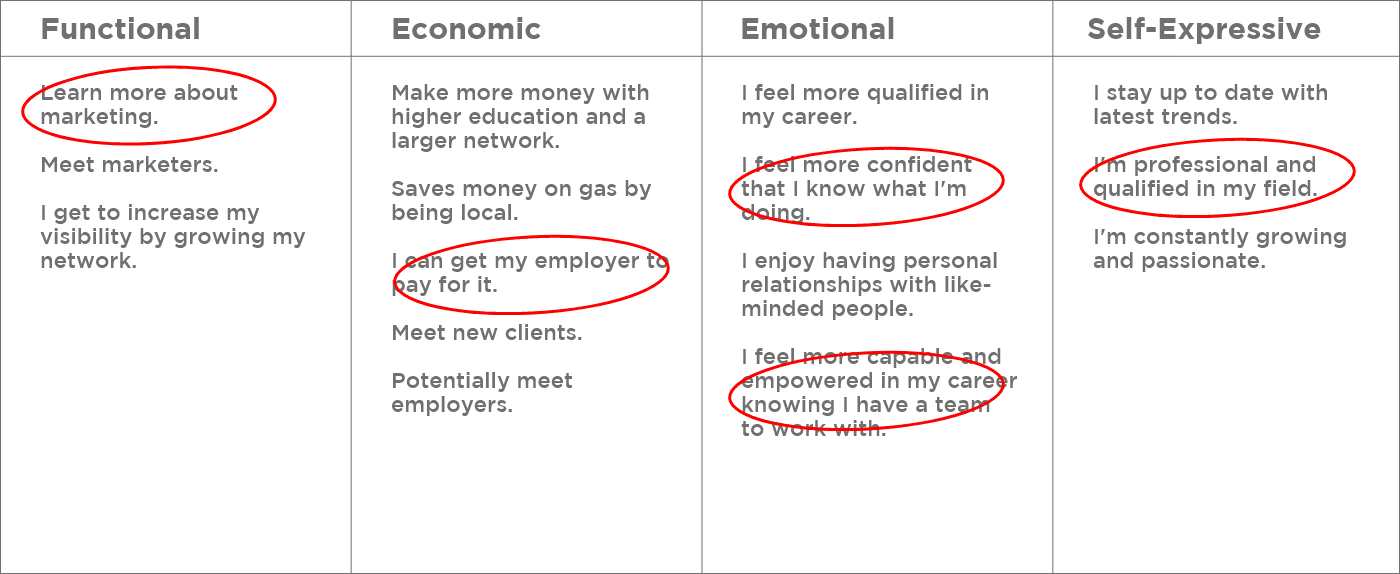

For the final step, narrow down which benefits you believe provide the most value to the customer. Marketing theory suggests your brand is strongest when it’s able to focus a single core message. At this point, it’s important to determine which of these are most valuable and which should be considered not important enough to advertise.

In the example above, we’ve selected five core brand drivers. While there isn’t a science to exactly how many should be circled, many suggest focusing on the single driver that your customers perceive as the most valuable. I suggest trying to stick to between one and five. More than that and your messaging risks becoming muddied and diluted.

For more about the brand driver process, check out the course Brand Foundations on LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com).

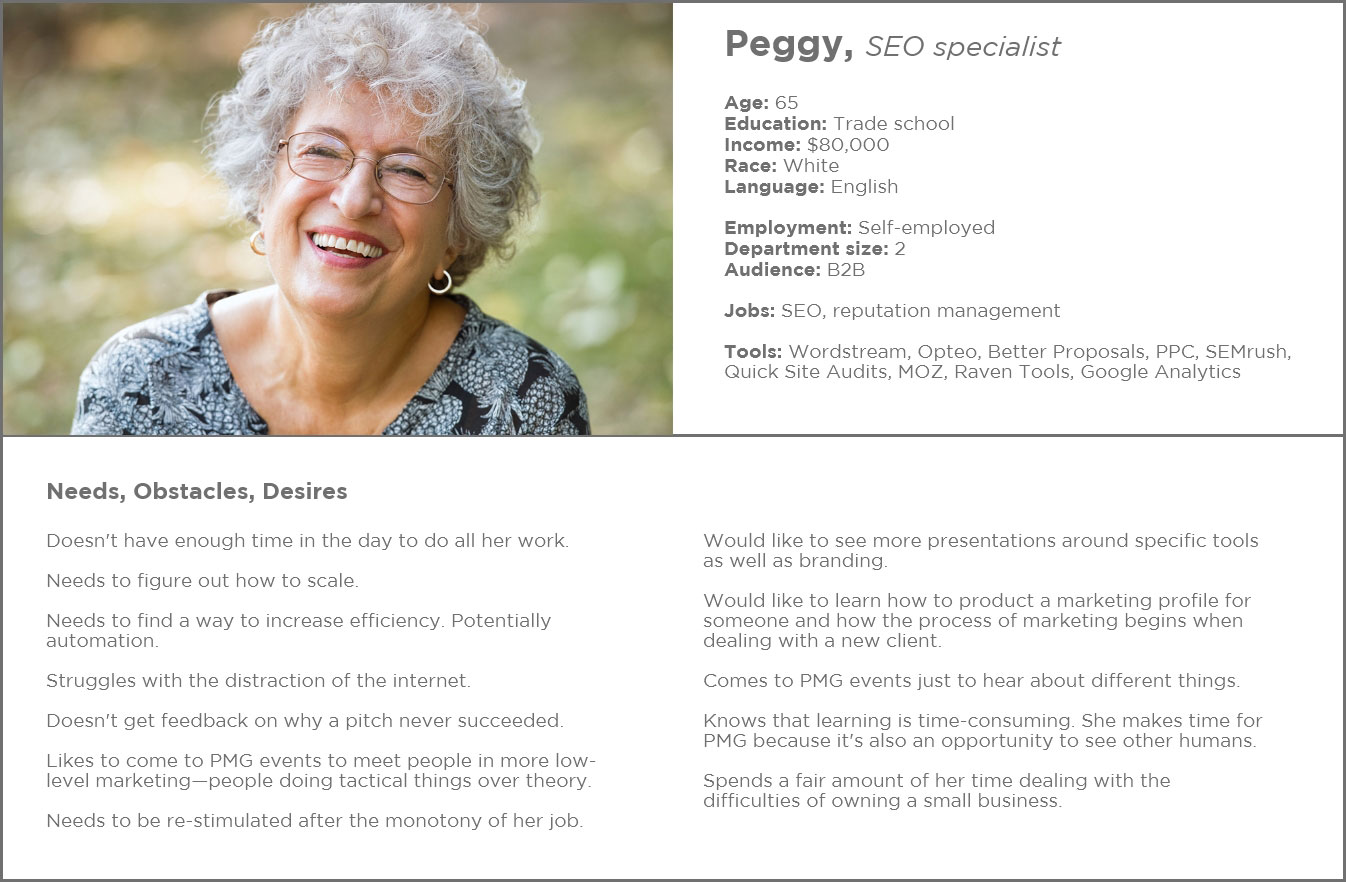

Proto Personas

A persona is a representation of a customer that can be used as a guide when designing a product. While most of us learned about personas as an outcome of user research, the Lean approach suggests we build personas based on assumptions as a method of getting started designing more quickly. Whichever method you choose, it’s important that Personas are ever-changing documents and will probably evolve over time.

A Proto Persona takes the Lean approach and prioritize speed over accuracy. Rather than spending a lot of time building a fully thought-out identity of a user, focusing on basic demographics, needs, obstacles, and desires provides enough information for the team to get started working. It’s more important that your team have a shared understanding of who is using your product and what overall hurdles your product is attempting to solve rather than expanding upon minor details that don’t provide an adequate return on investment.

Here’s an example of a proto persona I created for the PMG brand redesign.

For more on proto personas, check out the book Lean UX by Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden.

Hypothesis Statements

This is verbiage about hypothesis statements.

Define The MVP

Defining the MVP

Empathy Map

Empathy Map

Developing a Storybrand

Developing a Storybrand

Lightning Decision Jam

Lightning Decision Jam

Sprint

– Define the challenge (Day 1)

— Expert Interviews + HMWs

— Long-Term Goal + Sprint Questions

— Map

— Lightning Demos

— 3Part Sketching

—Note taking

— Doodling

— Crazy 8’s

— Concept

– Vote on Solutions (Day 2)

— Heat Map Vote

— Solution Presentation

— Straw Poll Vote

— Decider Vote

– The Storyboard (Day 2)

— User Test Flow

— Storyboarding

– Prototyping (Day 3)

– Testing (Day 4)

Hooked Model

Hooked Model

Prioritization Process (card sorting)

Prioritization Process

Design

Wireframing

Wireframing

Prototyping

Prototyping

Content Writing

Content Writing

Aristotle’s principles of persuasion

Content Writing